Displacement

Displacement is one feature of human language that strongly separates human language from the "languages" of non-human animals.

Displacement is the ability of human language to refer to things that are not in the here and now, that is, things not in our immediate reality.

The State of Mind Induced by Music

Hypothesis:

- The primary effect and function of music is to induce an altered state of mind in the listener.

- Music, especially "strong" music (where "strong" is necessarily relative to the listener's musical taste), creates in the listener a desire to partially disconnect from immediate reality, and to think about other things, things removed from immediate reality.

- The ability to disconnect from immediate reality in this way is beneficial, because sometimes, to get ahead in life, we have to think hard about how much we want things that are very different from what we have now.

The Evolution of Music

Hypothesis:

- The content of music has no intrinsic meaning – music constitutes a signal which induces the required mental state in the brain of the listener.

- Music, or more specifically the human response to music, has evolved from something else.

- Music has an obvious relationship with spoken language, and shares many of its individual aspects, such as rhythm, melody, and hierarchical structure. (And of course a significant portion of music contains singing, which actually is a stylized form of speech.)

- So if music evolved from something else, that "something else" was most likely some aspect of the human instinct for speech and language.

How Displacement Might be Learned

As an adult fluent in your native language, it is usually easy for you to determine if some particular element of spoken language refers to something not in your immediate reality.

Sometimes you know this because it is explicitly indicated by the use of words that refer to other places or other times, or by the use of words like "would", "could" or "should" that refer to possibilities which are not real, or not real yet.

Other times the reference to something beyond the here and now is implicit, because you know that whatever is being referred to is not actually in the here and now.

For an infant learning language for the first time, there is no way to know a priori whether any particular speech utterance refers to the here and now, or to something else.

In those cases where speech is about the here and now, the infant can observe what is being referred to simultaneously to hearing the relevant speech, and we can assume that this provides enough information for the infant to eventually learn the relationship between the two.

In the case of "displaced" speech, speech which refers to something not in the here and now, it's a bit more difficult.

One very simplistic (and very blunt) approach to solving this problem is that an infant's language-learning instincts could be programmed to assume that any speech that it hears might be displaced.

But this still leaves the problem of knowing what any such speech is referring to.

Continuing with the strategy of simplicity (and bluntness), let us suppose that the infant allows itself to freely think about things not in the here and now, whenever it hears someone speaking.

In some cases, if the thing being referred to was somewhat related to the current situation, then the infant's own thoughts might be something similar, and that might be enough, statistically over the long run, for the infant to determine the relationship between displaced speech and the things that such speech refers to.

To give a very simple example, if someone says "Would you like to eat some ice cream?", and the infant happens to be thinking about what it would like to eat, that might be enough to help make a connection. (Of course it would help even more if actual ice cream appeared shortly afterwards.)

The Evolution of Music as a Disabled Pseudo-Language

I have suggested a possible reason why an infant learning its first language would be helped by an alteration of mental state which encourages thinking of things beyond immediate reality.

To account for the evolution of music, it is only really necessary for there to be some reason why this alteration of mental state would help an infant learning language. (Ideally this would be confirmed by observing such an alteration in mental state in practice, if there is some way to practically and safely make such an observation on live human infants.)

First Speech, Then Music

The full evolutionary scenario is then as follows:

- When an infant is learning language for the first time, hearing speech induces a mental state which encourages it to think about things beyond immediate reality.

- Somehow, this alteration of mental state helps the infant to learn language.

- When language acquisition has progressed beyond a certain point, ie when the infant has learned how to determine that speech is referring to things beyond immediate reality, there is no longer any reason for the altered mental state to be induced by the occurrence of normal speech.

- However, the benefits of being able to voluntarily and temporarily enter this mental state continue past the time when language is being learned.

- Music evolved as an altered form of language which induces this mental state, even when "normal" language has ceased to do so.

Possible Confusion between Music and Language

One thing we can readily observe about infants is that they do respond to music.

If normal speech is inducing a certain mental state, and music is inducing the same mental state, possibly stronger, then there is room for confusion.

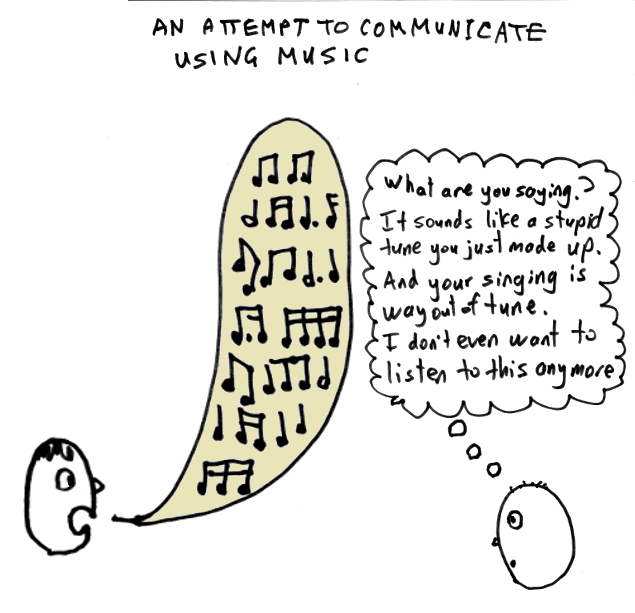

In particular, the infant might start learning about music as if it was a language.

Which would be wrong.

Music does seem to be like a language, and people talk about it being the Universal Language, etc etc.

But in practice people do not use music to communicate information, and for the most part people listen to music, not to receive information about something, but rather to experience the associated alteration of mental state.

A plausible explanation for this uncertain relationship between music and language is that music started out as something very language-like (or indeed, actual language), but then evolved into something not functional as a language, but retaining enough language-like features that we can still see the resemblance to the language that it evolved from.

The Constrainedness of Music

One thing that distinguishes music from spoken language is that it is much more constrained.

For example, if you are listening to a four minute musical item, and you've already heard the first two minutes, most of what's in the second half will be very similar to what you've already heard, much more so than you would expect with normal conversational speech.

We can also compare the difficulty of making "good" music with that of speech. Most of the music that most people listen to is from a very limited number of items performed and produced by a very limited number of highly practised professionals. For many people, almost none of the music that they choose to listen to is written or performed by "amateurs".

Whereas, with speech, a substantial portion of the speech that we listen to is produced by ordinary people that we happen to know, and for the purposes of conversational speech, there is no meaningful distinction between amateur and professional (ie "professional conversationalist" isn't really a thing, or if it is, it is very contrived).

These differences can be described more technically in terms of syntax and generation:

- There is evidence that the human brain responds to musical errors similarly to how it responds to syntax errors in speech. However, no one has ever described a "syntax" for music that accounts for the set of musical items that people want to listen to, other than the very simplistic syntax as defined by an explicit list of all known musical items.

- Unlike with speech, listeners to music do not develop an ability to freely generate new valid utterances, if by "valid" we mean music as good as the music that people normally listen to.

- Even with known examples of music, it is very difficult to perform an item of music to a "good enough" level of quality, and a lifetime of practice is typically required to achieve an adequate performance.

Science has not yet determined the exact nature of the constraints that distinguish between what is musical and what is not musical.

(When Science does solve this problem, human composers will probably get replaced by software, and the software might be so good that a substantial portion of the human race becomes pathologically addicted to music. But that hasn't happened yet.)

Constrainedness => Not a Language

These extra constraints – whatever they may actually be – render music unusable as a system of communication. If there are at most a few million known good tunes (and probably much fewer in pre-technological societies), and if each item has to last at least a couple of minutes, then the overall bandwidth is going to be very low if you try to use musical performance as a communication system.

(If you really feel the need to do the math: one tune chosen out of a million, playing a new tune every 2 minutes, would translate to 20 bits per 2 minutes = 10 bits per minute = 1 bit every 6 seconds, which is very slow, compared to, for example, normal spoken English, which would be at least 1200 bits per minute = 20 bits per second.)

Given that the content of music has no known intrinsic meaning, and given the hypothesis that it is only the effect of music on our mental state that matters, it is plausible that music has evolved these constraints precisely in order not to be usable as a language.

(A secondary reason for music to be strongly constrained is that too much music might be a bad thing, especially if it leads to the listener always being disconnected from immediate reality, so the intrinsic difficulty of composing and performing music helps limit the amount of time spent listening to music.)

Conclusion: The Relationship between Language and Music

In summary, my hypothesis about the relationship between language and music is as follows:

- The human brain has evolved a response to speech, which occurs during the period of time that an infant is learning its native language, and which induces an altered mental state that involves an increased tendency to think about things beyond immediate reality.

- After a certain amount of progress in language acquisition, this altered mental state is not of any further benefit to the language learning process.

- However, the ability to temporarily and voluntarily enter this same mental state (while not being in that state all the time), continues to be of some benefit, because it encourages people to think, at least some of the time, about things that are possible, and not just things that are real or things that are certain to happen.

- Music has evolved as an altered "pseudo-language", one which remains able to induce this altered mental state in the listener, even after that mental state is no longer relevant to language acquisition.

- Additional constraints have evolved, as part of the criteria for musicality, which render music unusable as a system of communication – this helps prevent any confusion with actual language.